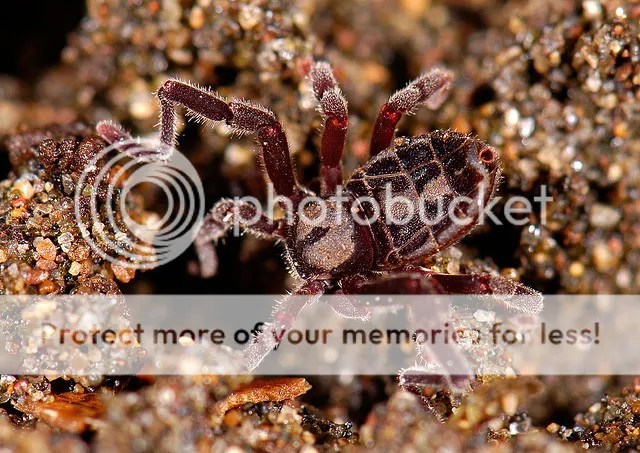

Hooded tickspiders.

Yes, I can sense the readers of this entry promptly throwing in the towel, giving up on life itself at simply reading the name of such a creature. Let the idea that Mother Nature is a nurturing, caring force be put to bed immediately, for evolution has crafted the cruel curveball that is the hooded tickspider; equipped with all the charm of a blood-gulping, parasitic tick, and the charisma and affability of a spider. Why even bother leaving the house at this point, what with such unholy, Dr. Moreauian amalgamations walking around? What’s next, cobra-tigers? Leech-sharks? Manbearpig?!

While it is certainly anxiety-inducing to contemplate an animal that seemingly exists as two highly-loathed arachnids essentially smushed together, as if done so to be an entry in a competition to generate the most unsavory Doritos Collisions flavor marriage of all time, in reality, this isn’t the case at all. Just as antlions are neither ants or lions, and dragonflies aren’t dragons, and aren’t really ‘flies’ either, the hooded tickspider represents a unique breed of creature, distinct from both ticks and spiders. Hooded tickspiders belong to a small order of arachnids; Ricinulei. There are about sixty species worldwide, making Ricinulei currently the least speciose order of arachnids, but more species are discovered as the years go by.

If you are breathing a sigh of relief as horrific imagery of web-weaving blood-suckers with no other mission than to patiently wait for you underneath the lip of your toilet seat peacefully leaves you, don’t get ahead of yourself. While hooded tickspiders are no threat to people (for a number of reasons related to their anatomy and extreme cryptic nature), they definitely provide enough innate, unnerving creepiness to make up for it.

Given the miraculous chance that you would encounter one of the few dozen species on Earth in the wild (which would inevitably involve you rooting around in the dirt and leaf litter for weeks in West Africa or the tropical Americas…because those are the only places they are found…and infrequently, at best), the hooded tickspider would probably yield more disappointment than colon-emptying terror. Truthfully, they aren’t much to look at if you aren’t familiar with what to look for. You won’t likely find anything even rivaling the size of the nail on your pinky finger, and they have all the brash coloration of a burlap sack. A captured, tiny, soil-caked hooded tickspider, curled into a defensive, ball shape, would be virtually indistinguishable from your common garden spider to the untrained, non-arachnologist eye.

However, if you were to take a closer look, you would quickly find that the pathetic, trembling critter in your hand appears to be missing something relatively important.

Like a head.

If this still-living animal were a vertebrate, and not an arthropod, you would probably be bounding off into the forest like fucking Ichabod Crane. But no, you, hypothetical, intrepid naturalist-person, know that arthropod nervous systems aren’t nearly as centralized in the head region as the nervous system belonging to cats, dogs, horses, and ourselves. Shit, cockroaches can live for weeks without their heads, in true Steven Seagal, “Hard to Kill” fashion. Perhaps that is what’s going on with this little guy? Maybe the head is nowhere to be found, but the body hasn’t caught on yet?

Well, that’s not correct either. It’s not so much that hooded tickspiders “took a little too much off the top” evolutionarily, it’s just that the “head”, or rather, all the parts associated with it, is obscured by a structure that is the origin of the first part of their common name. In the place where you’d expect to find head-bound organs found in the vast majority of normal, Earthling animals, there’s simply…nothing. Just a flat, exoskeletal plate. It’s like if your body was normal all the way from your feet up, but stopped abruptly at a goddamn manhole cover resting on your shoulders. This plate is known as the “hood” (and to arachnologists, the “cucullus”, which is Latin for “cowl”).

And of course, perpetually faceless, dark, hooded individuals are generally stand-up, good-natured characters. Nothing to fear at all.

So, the question becomes: what in the hell are tickspiders hiding under there? What secrets are they keeping from us? Well, you can sure as shit bet that it isn’t jelly beans or chocolate or anything remotely pleasant. Just like a manhole cover, this “cucullus” is movable, and if retracted reveals…not a whole lot, actually. The big “surprise” is a vacant mouth opening under there, along with a pair of chelicerae (mouth “parts” that are standard for all members of the subphylum Chelicerae) that end in sharp little claws, and that’s about it.

Hooded tickspiders don’t even have eyes, above or below the cucullus. But, despite being completely peeperless, they are highly sensitive to light, and likely achieve this capability through photosensitive cells placed laterally along their hard, outer cuticle (ancient, fossil species had eyes in these locations, but as hundreds of millions of years have gone by, the eyes appear to have been reduced). But as for discerning their immediate surroundings and navigating through their humid, forest floor world by way of light-based vision? Not happening. Hooded tickspiders blindly clamber along the leaf litter, fumbling around and feeling for any small insect or other critter in its path. It is then believed to snatch up the unfortunate morsel with its pair of small, delicate, claw-tipped pedipalps (the same appendages that have been modified into thick claws in scorpions), and then proceeds to stuff pieces of the hapless victim into its empty, butthole-like mouth. They are diminutive living tanks, half the size of the keys on your computer keyboard, yet covered in a heavy, air-tightly riveted together exoskeleton so extensive and impenetrable that it instead of a normally vulnerable face, it has a vault door. Like some kind of goddamn arachnid Death Star, it has a single observable opening, a tiny, tangible chink in its fortification…and even that is constantly shut up in the biological panic room formed by its “hood.” Up close, they look more like a human-crafted vehicle than a legitimate animal, appearing to simply be missing headlights and a grill.

Outside of the strange head region, the anatomy of members of the order Ricinulei is fairly normal compared to most arachnids. Sure, the exoskeleton is hard and super-durable, but the general body blueprint (sometimes referred to as a “bauplan” by biologists) fits the arachnid archetype. Cephalothorax (including head organs…or what remains of them), abdomen, eight pairs of walking legs…the works.

However, some elements of the 2nd and 3rd pair of legs are a bit odd in many species of hooded tickspider. For instance, the 2nd pair of legs is typically elongated, and leads far to the front when the animal is walking; it is thought that these legs act as sensory organs in a way, carefully guiding the animal by an acute sense of touch. The males of many species have even larger 2nd pair of legs, with hyper-muscular, comically bulky segments. These limbs may be used in male-to-male combat, where the two individuals would likely jostle with each other using them, perhaps trying to push the competitor aside or into a position of inevitable submission. This aggressive, competitive behavior is ubiquitous in the animal kingdom, and is observable in the clashing antlers of male deer, the brutal whipping of necks between male giraffes, and pretty much any weekend at a collegiate fraternity party when alcohol, in any amount, is consumed.

The 2nd walking limb morphology of males of this species (Pseudocellus chankin) has been described in the literature as “hella swoll, brah”

So, the 2nd pair of walking legs in hooded tickspiders tend to be modified, albeit in different ways and degrees, in both males and females. However, the 3rd pair of walking legs, in males, has evolved to carry out a very gender-specific function. In males, these legs end in a weird, fan-shaped cluster of nubby projections that form a scoop. During hot, hot hooded tickspider sex, the male uses these scoops like a lacrosse stick to cup and manipulate a spermatophore (a solid, gelatinous mass of sperm, basically; commonly used in arthropod reproduction, especially in arachnids), and then, once in position, lovingly crams it into her ovipore. So, it’s less like familiar, human sex and more like spackling a hole in a wall, but hey, apparently it’s been working for hundreds of millions of years just fine. You would be wise in pitying the female hooded tickspider, whose pinnacle of romantic experiences involves a clumsy, blind mate bumbling towards her lustfully, with fistfuls of his own spunk.

“…ladies?” *wink*

After a hasty copulation, and reception of the male’s seed fastball has occurred, the female lays a single, fertilized egg. This egg is then stored underneath the “hood” until it hatches sometime later, into a six-legged, soft-bodied larva that, over a surprisingly long amount of time, progressively molts into an eight-legged mature form. The intimate care that the female provides this single offspring represents a fairly rare parental tendency within arachnids, although it is similar to the motherly devotion to progeny exhibited by whip-spiders (something I examined in the first entry in this series on arachnids). Undoubtedly, carrying the egg in that tight area between the cucullus and mouth for so long is burdensome for the mother, and is a sacrifice that I would consider of evolutionary significance. It would be interesting to examine the long-term fitness consequences of the female hooded tickspider’s habit of stuffing their eggs underneath their face plates.

Fuck off, Easter Bunny. This hiding spot’s taken.

Perhaps the oddest thing about hooded tickspiders isn’t their outward appearance, but their strange legacy of discovery and their evolutionary history. The discovery of the order Ricinulei occurred in 1837 in England as a fossil representative from roughly 300 million years ago. It was originally misidentified as a beetle in the original literature, but it was soon revealed to actually be representative of a previously unknown group of arachnids. Only a year later, a living species was discovered in West Africa, making hooded tickspiders one of the few groups of animals on the planet who were first described through fossils of extinct species, and only later on observed still hanging out, alive, in the modern era (a more famous example of this situation is the coelacanth).

This is sort of the equivalent of suddenly discovering living Triceratops in some remote region of the tropics…except, you know, way less awesome.

As far as we can tell, Ricinulei is a very old group, dating back to at least 320 million years ago or so, and they’ve changed remarkably little since that time. As for their place in the arachnid family tree, two main lines of thought currently exist. The first is that hooded tickspiders are most closely related to the group containing mites and ticks (subclass Acari). This is based on similarities in early development (the six-legged larval stage is shared between tickspiders, ticks, and mites), as well as similarities in their mouthparts. The other competing hypothesis is that Ricinulei represents an old, still-surviving arm of a long-since extinct group of arachnids known as trigonotarbids. The order Trigonotarbida existed from about 400 to 300 million years ago, and was made up of arachnids vaguely similar in body shape to spiders, but with many plates (called “tergites”) running down the abdomen and no ability to produce silk. According to paleontological evidence, both trigonotarbids and hooded tickspiders had/have curious claws on the tips of their pedipalps, and a unique mechanism joining the two halves of the body is found in both groups, and exclusively so.

Wherever the hooded tickspider lineage comes from, there is no doubt that living representatives are among the oddest, and least understood, arachnids we have around. We are slowly learning more and more about these enigmatic little, faceless beasties, and we are continually revealing additional information about their strange life histories, diets, and origins. While I find them unavoidably fascinating, none of this makes them less unsettling, however, in my book. If you feel the same as me, and you fear your nightmares will inevitably be filled with armies of functionally decapitated, eight-legged, sperm-chucking, spidery demon-spawn after reading this entry, just let the following visual of Eowyn vanquishing a hooded menace play in your head as you peacefully drift off to sleep tonight.

Yeah. That’s the stuff.

Image credits: Opening hooded tickspider, Pseudocellus chankin

© Jacob Buehler and “Shit You Didn’t Know About Biology”, 2012-2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jacob Buehler and “Shit You Didn’t Know About Biology” with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Best Biology article I have ever read. Very engaging and wonderfully descriptive.

Pingback: Arachnids: Pseudoscorpions | Shit You Didn't Know About Biology

Pingback: Viikon outo eläin: salamyhkäiset päättömät hämähäkit | Erään planeetan ihmeitä

Pingback: Arachnids: Harvestmen | Shit You Didn't Know About Biology

Pingback: Arachnids: Solifugids | Shit You Didn't Know About Biology

Pingback: Arachnids: Vinegaroons | Shit You Didn't Know About Biology

Wonderful article! 🙂